|

| The good ole days |

It’s a debate as old as the internet: One space after the

period, or two? I was surprised to learn

that this is a difficult question to answer.

Half the people I’ve spoken with add two spaces after a full stop. The other half raise an incredulous eyebrow

and tell me that one space is not only preferable, but get morally indignant

that I even asked. I kid a bit, but in

all seriousness, if you were to ask Plato which is better, he might tell you

that a single space correlates most closely with the Ideal manuscript formatting.

So what’s the deal?

Turns out the biggest part of it has to do with when you learned to

type. If you learned to type on a

typewriter (or shortly after word processors were introduced) you probably add

two spaces after the full stop to accommodate the monospacing font on the

typewriter. More simply, when the

striker on a typewriter impacts the paper, the letter takes up the exact same

amount of space as any other. So the I

you type occupies the same space as an M.

That’s not the case when you type on a word processor, whose fonts are

variable (and may or may not have serifs).

If we extend that to the present, most documents are not

only produced on word processors, but are also published online. The digital revolution produced a

surprisingly homogenous landscape, with writers forced to learn new rules. But, in the early days of internet

publication, no one had yet figured out just how to format their writing. You can still sometimes see this, if you type

something on Word and then post it straight to a blog site—the pagination is

strange and sentences are broken up at odd places. This led to a revision in publishing

expectations: now writers were expected to accommodate the internet by only

inserting a single space after a period.

|

| The not-so-good ole days |

Turns out, this is all just another one of those

generational divides with everyone over thirty on one side (and who trusts us

anyway?) and those meddling kids (I would have gotten away with it too, if it

weren’t for them!) on the other.

But I don’t like a single space at the end of a

sentence. It feels constricting. A sentence ought to be more than an

expression of fact, it ought to reflect certain aesthetic choices. In a sense, how you write ought to

communicate as much about your understanding of beauty and the way the world

operates as it does about the simply communicating information. This, of course, is a stylistic choice.

Style is tough to communicate. As tough to communicate as to teach. Strunk and White tried it, and Stephen Pinker

chastised his colleagues in the sciences over their (lack of) style. The basics of any style can be printed in a

book and remonstrated against in lecture halls. Omit needless or useless words; avoid cliches

like the plague; death to hyperbole! You

get my drift. Harder to instill a style

that is completely your own. Your style

reflects your voice. Maybe it’s

conversational, perhaps it’s academic; it could be cold or warm or informal or

meandering. It should never be

cookie-cutter.

|

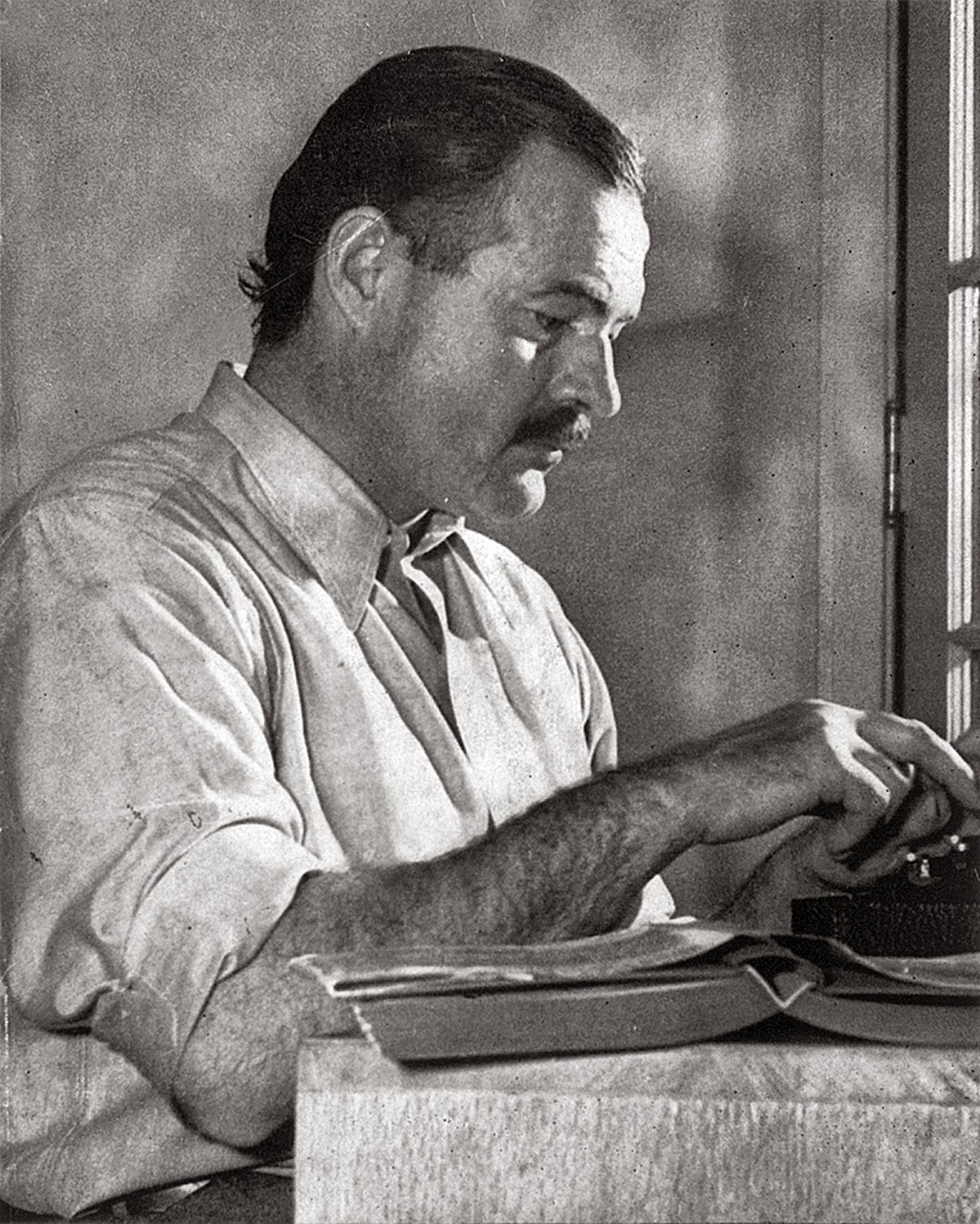

| Hemingway on a typewriter |

That last bit is the hardest to deal with, though, since it

demands constant attention to craft and on-going refinement. Hemingway and Faulkner are both known for the

way in which they wrote their stories, as much as the plot or characters

themselves. But they had to listen to

criticism, take advice, ponder, reflect, edit, rework. In the end, their style is as much a part of the narrative as the plot is.

Which brings me back around to tapping out space-space when

I come around to the end of a sentence.

I like the space it gives me (pun, of course, intended). There’s a little bit of additional room

to breath, a blank space into which I

can insert my thoughts and reflections on what I’d just read. It indicates to the reader that she should

savor what I’ve offered.

We live in a cramped world where experiences flash at us at

60 miles per hour. Faster,

sometimes. If I only wanted to

communicate facts, I would have written them as bullet-points. I don’t.

I want you to experience my words as a reflection of who I am, to engage

in a conversation with me.

The dialogue that we construct together is tenuous, at best,

but it is part of the long, strange process of becoming a person capable of

introspection. Ultimately, it’s about

you and me sitting down together to share our thoughts.

I’ve changed as much writing as you have reading (I hope)

and those two little spaces at the end of the sentence have facilitated, in

their own humble way, that process.

So type on, I say.

Type on.