Friday, August 31, 2012

We've Gone International . . . Multi-National!

This week marks "Sometimes I Feel Pretentious" getting just a little more pretentious. This week, Australia finally stopped by to say "'ello, mate!" This brings the current continental count up to six: North America, South America, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. I'm hoping to eventually get Antarctica but I'm willing to put that goal on hold until their population increases. Nonetheless, if you know anyone in the Antarctic, give 'em a holler and tell them to check out my blog. To everyone else, thanks for your continued reading! Let's keep it going strong!

Doctor Who Series Seven . . . Pond Life Part 5

No Easy Day . . . During An Election Year

"No Easy Day," a book detailing the raid in which United States Navy SEALs violated Pakistani sovereignty, and ended in the death of Osama bin Laden, will be released September 4, 2012. Hyped as much by the fact that it's pseudonymous author, "Mark Owen" has been outed as Matt Bissonnette, the book purports to divulge secrets that contradict official reports by the Obama administration. According to the Washington Post, Pentagon officials have begun pursuing legal measures against Bissonnette.

Those are some of the more tawdry details. What I find fascinating is a comment made by Fox News Executive Vice President and Executive Editor John Moody who declared authors of books have no expectation of privacy. The Associated Press and others have gone on record saying that (to paraphrase) once the horse is out of the barn don't bother shutting the door. Once Bissonnette's name was broadcast it was no longer necessary to protect his identity. Others, notably CBS News Chairman Jeff Fager, who took pains to hide Bissonnette's identity in his outlets, despite the leak elsewhere. I admire his moral courage. While I personally side with the AP (as you can clearly see in this post), Fager makes a remarkable point in this day and age of WikiLeaks and information overload: Sometimes you should stick to your guns because it's the right thing to do.

This is an election year. As such, it's a year wherein normally even-minded people will resort to name-calling and emotional terrorism in order to prove they're right. I can't wholly abstain, though I'll try. Living in a dual-party political system has its advantages, but one of the disadvantages is that once the nominees are locked in, they're basically all you've got.

Someone once exhorted me to write in my own name on the ballot if I didn't like either candidate, and he was excoriated for his call to "split the vote." Indeed, there's some wisdom in this; we're reminded that the lesser of two evils is the better deal. Really? Maybe you've heard that cliche so many times that it has lost its meaning. Because what you're telling me is still to pick an evil. Something that no good and right person should ever willingly choose.

We've been told that the only way for evil to exist is for a good men to do nothing. Or maybe just to choose the lesser of the evils. Maybe it is time to stand up and say no to both. Perhaps we won't win. Perhaps the path is narrow, but surely it's better than that grand boulevard heading to hell. So, way to go, Fager, for sticking to your guns and deciding to keep Bissonnette's name confidential. And go ahead, all you anonymous vote-splitters. Show us what courage looks like. And hey, buy "Mark Owen's" book; it'll help him pay his legal bills.

Those are some of the more tawdry details. What I find fascinating is a comment made by Fox News Executive Vice President and Executive Editor John Moody who declared authors of books have no expectation of privacy. The Associated Press and others have gone on record saying that (to paraphrase) once the horse is out of the barn don't bother shutting the door. Once Bissonnette's name was broadcast it was no longer necessary to protect his identity. Others, notably CBS News Chairman Jeff Fager, who took pains to hide Bissonnette's identity in his outlets, despite the leak elsewhere. I admire his moral courage. While I personally side with the AP (as you can clearly see in this post), Fager makes a remarkable point in this day and age of WikiLeaks and information overload: Sometimes you should stick to your guns because it's the right thing to do.

This is an election year. As such, it's a year wherein normally even-minded people will resort to name-calling and emotional terrorism in order to prove they're right. I can't wholly abstain, though I'll try. Living in a dual-party political system has its advantages, but one of the disadvantages is that once the nominees are locked in, they're basically all you've got.

Someone once exhorted me to write in my own name on the ballot if I didn't like either candidate, and he was excoriated for his call to "split the vote." Indeed, there's some wisdom in this; we're reminded that the lesser of two evils is the better deal. Really? Maybe you've heard that cliche so many times that it has lost its meaning. Because what you're telling me is still to pick an evil. Something that no good and right person should ever willingly choose.

We've been told that the only way for evil to exist is for a good men to do nothing. Or maybe just to choose the lesser of the evils. Maybe it is time to stand up and say no to both. Perhaps we won't win. Perhaps the path is narrow, but surely it's better than that grand boulevard heading to hell. So, way to go, Fager, for sticking to your guns and deciding to keep Bissonnette's name confidential. And go ahead, all you anonymous vote-splitters. Show us what courage looks like. And hey, buy "Mark Owen's" book; it'll help him pay his legal bills.

Thursday, August 30, 2012

Doctor Who Series Seven Prequel . . . Pond Life Part 4

The Ood make for great housekeepers, but it seems like Rory can't quite handle a manservant. To tell the truth, I'm not sure how I'd feel having someone doing my cooking, cleaning and other chores without a red nickle to go for it. From everything we've been told, however, the Ood seem to enjoy it, so who knows? Maybe I'd give it a go.

Wednesday, August 29, 2012

Doctor Who Series 7 Prequel . . . Pond Life Part 3

In which our loveable gang encounters an Ood, on the lieu.

H+ Update

|

| http://www.atomicmpc.com.au/News/311420,new-web-series-h-is-essential-sci-fi-viewing.aspx |

While I'm still worried they may not be able to pull this off, I'm a starting to become hopeful that it might be something worth watching. In fact, I'd recommend you check out their YouTube page and take a look.

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Doctor Who Series Seven Prequel . . . Pond Life Part 2

Here's the second bit of the BBC prequel to Doctor Who series seven, in which the Doctor busts in on Rory and Amy in bed, to reassure them (poorly) that the future is just peachy.

Uncharted 3: Drakes Deception Review

I have mixed feelings about this game. On the one hand, had I never played the first two Uncharted games I probably would have considered this a pretty decent offering from Naughty Dog. But since I have played those first two games, and I saw how far they came with the second game, I don't think the third game lived up to them.

The game begins in the rough and dirty streets of London, where Nathan Drake and his vigilant companion Victor "Sully" Sullivan, are double-crossed in a pub over the ring Drake wears round his neck. Things go sour, and Nathan and Sully are both shot--cut to flashback of Nathan as a much younger man, and his introduction to Sully.

From that flashback we learn not only how the two met, but how Nathan acquired the ring in the first place, and the key to a treasure Sir Francis Drake has hidden not only from his Queen, but also from the world. So it's up to our adventurers to go find it, chased doggedly (and providentially) by their foes.

Other reviewers have commented on the game's lackluster graphics and characterizations compared to the second game, and I tend to agree with them. I've stated elsewhere that I have no fondness for third-person shooters. I find them clunky. But while I could countenance those flaws in the second game because of its phenomenal story-telling--using the third-person as part of the story--the third game simply fell flat. Yeah, each set felt wonderful, and the game was relatively immersive; nonetheless, it still felt a little underwhelming. Because this was released as 3D compatible, I have to wonder if Naughty Dog diverted some of its energy from making a great game, and invested it in implementing new technologies. I haven't seen the game in 3D, so my opinion is colored, but from what I have seen I wish they'd put their eggs in a different basket.

So, while I think it was fun to see Nathan Drake fight never-ending hordes of baddies, and uncover centuries old secrets, it wasn't that much fun. From the initial chapters, I expected this to be more character driven, offering a sense of why Nathan is who he is. The danger never felt real, I never expected to have to sacrifice to win, and the threat to the world bit was just . . . not that threatening. Besides that, the two climaxes are fought via cut-scene, and when you do get to fight, it's an anticlimax that leaves you feeling cheated.

In the final analysis, I'd recommend this game if you've already played the first two, but I wouldn't recommend buying it (unless you really dig on the multiplayer, which I don't care for).

As an aside, I really hate how they modeled Elena in this game.

Monday, August 27, 2012

Space Stallions . . . In Space!

What originally began as a school film project quickly metamorphosed into awesome! A parody of just about every 80s movie you can shake a keytar at, see how many wild tropes you can wrangle. Just be careful not to harass the next horse you see with existential angst.

When you're done watching, and loving it, head over to the creators' Facebook page to show your appreciation.

Doctor Who . . . Pond Life

Head on over to BBC's YouTube page to check out the five-part webisode prequel to series seven of Doctor Who. En route to return to the Ponds, something goes wrong and the Doctor pops up all over time and space. We're promised familiar faces and worn out places (wait, that's an 80s pop hit). Nonetheless, it looks to be a fun build-up to the beginning of series seven.

Those Across the River Review

Fleeing the North in disgrace, WWI veteran and failed academic Frank Nichols and his soon-to-be wife Eudora, arrive in a tiny Georgian hamlet where Frank has just inherited the home of his recently deceased aunt. Under the strict injunction to sell the house and absolutely not to move to Whitbrow (the aforementioned tiny hamlet), Frank does exactly the opposite. But haunted by the specter of war, and the stigma of both cuckoldry and adultery, Frank takes this opportunity to be heaven-sent. It doesn't hurt that just across the river is the ancient Savoyard plantation, where his great-grandfather was known to have treated his slaves so inhumanely, that they eventually rose up and slaughtered him. Hoping to segue family tragedy into a book which might serve as passport back to his academic career, Frank is lured across the river and confronted by memories that simply refuse to die.

This very basic summary hardly does the book justice. First of all, this is a supernatural horror story, and is currently up for nomination to win the World Fantasy Award. Second, it deals with subject matter far more literary than this genre is used to. The mental wounds that Frank suffered in the trenches of WWI still torment him; moreover, from the outset we're informed that while he's a nice guy, he's not above sleeping with another man's wife. From this fragmented moral landscape, we're also offered a piquant reminder of the suffering and inhumanity of slavery.

This book is remarkably smart, not only in its subject matter, but also in the way that it deals with the persons of Frank and Eudora Nichols (as they eventually do marry). Told in the first person, however, it necessarily focuses on his triumphs, defeats, fears and the quotidian tragedies that comprise human existence. It doesn't surprise me at all that this book has been picked up to be made into a movie, directed by Tod "Kip" Williams, who directed Paranormal Activity 2. Commentators have noted that Christopher Beuhlman writes like a combination of Flannery O'Connor and Stephen King, which is not an inapt comparison.

The singular flaw in the novel, however, comes late in the second act, and continues throughout the third act. Once the mystery is revealed, and mortal lives are placed in danger, Beuhlman fails to utilize the wealth of characterization he has developed in the previous act. Indeed, the first act reads so well because of the deeply characterized human beings who inhabit the fictional world of Whitbrow. Their deaths, when they come are tragic, but we never have a sense of who they are under pressure; indeed, by the start of the third act they have simply disappeared and two new characters are introduced to help our protagonist win the day.

But this shortcoming is minor, and really only occurred to me after the fact. It hardly detracts from the overall story. It kept me up well past my bedtime and I can't say that I minded. In fact, this might be my favorite book of the year and I heartily recommend it.

This very basic summary hardly does the book justice. First of all, this is a supernatural horror story, and is currently up for nomination to win the World Fantasy Award. Second, it deals with subject matter far more literary than this genre is used to. The mental wounds that Frank suffered in the trenches of WWI still torment him; moreover, from the outset we're informed that while he's a nice guy, he's not above sleeping with another man's wife. From this fragmented moral landscape, we're also offered a piquant reminder of the suffering and inhumanity of slavery.

This book is remarkably smart, not only in its subject matter, but also in the way that it deals with the persons of Frank and Eudora Nichols (as they eventually do marry). Told in the first person, however, it necessarily focuses on his triumphs, defeats, fears and the quotidian tragedies that comprise human existence. It doesn't surprise me at all that this book has been picked up to be made into a movie, directed by Tod "Kip" Williams, who directed Paranormal Activity 2. Commentators have noted that Christopher Beuhlman writes like a combination of Flannery O'Connor and Stephen King, which is not an inapt comparison.

The singular flaw in the novel, however, comes late in the second act, and continues throughout the third act. Once the mystery is revealed, and mortal lives are placed in danger, Beuhlman fails to utilize the wealth of characterization he has developed in the previous act. Indeed, the first act reads so well because of the deeply characterized human beings who inhabit the fictional world of Whitbrow. Their deaths, when they come are tragic, but we never have a sense of who they are under pressure; indeed, by the start of the third act they have simply disappeared and two new characters are introduced to help our protagonist win the day.

But this shortcoming is minor, and really only occurred to me after the fact. It hardly detracts from the overall story. It kept me up well past my bedtime and I can't say that I minded. In fact, this might be my favorite book of the year and I heartily recommend it.

Friday, August 24, 2012

Fifty Shades of Crazy?

Last week saw sales for E.L. James's erotic "Twilight" fan-fic Fifty Shades of Grey fall to tenth place on Publishers Weekly bestseller list. Bolstered by strong internet sales in its early weeks, and then by selling her soul to the Devil (probably), Fifty Shades has continued to hold the top three slots in Top 10 Overall, Trade Paperback and the number two slot in Audiobooks for the year. Amazon sales continue to maintain their juggernaut status, with the collected trilogy continuing to sell well. The runaway bestseller has spawned numerous imitators, and left the rest of the world scratching their heads. The camps of those who love it and those who find it less than rubbish seem as divided as the Tea and Democratic parties.

So what's going on?

In 1841 Charles Mackay wrote a book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, describing the paroxysms of stupid into which people sometimes work themselves. His book popularized the strange phenomenon that occurred in the Netherlands in late 1636 and early 1637 when people went crazy for tulips. Sometimes called Tulipomania, at its height a single tulip bulb could sell for ten times the average income of a skilled craftsman. We recognize the phenomenon as an economic bubble, and we're still falling prey to it today. Mackay continues by examining a number of popular delusions to which we're still (more or less) prey: "alchemy, crusades, witch-hunts, prophecies, fortune-telling, magnetisers (influence of imagination in curing disease), shape of hair and beard (influence of politics and religion on), murder through poisoning, haunted houses, popular follies of great cities, popular admiration of great thieves, duels, and relics."

Now, while the tulip mania had some sort of basis in reality, and built on false hopes of government intercession, at its base it was an economic bubble. People were getting rich, and hoped that they would continue to get rich. So at least people were going dumb for something tangible. The rest is simple superstition, which nonetheless motivates more people than we'd like to account for. Recent statements by a Republican nominee seem to indicate that some people, as my training instructors liked to say, are still "stuck on stupid."

It would be irresponsible of me to conclude that fans of Fifty Shades are simply ill-educated or lacking mental faculty. The epithet of "mommy porn" has been applied to these stories often, and not just by literary detractors. Feminists have argued that this sort of depiction undermines much of their work over the last half century, relegating women to subservient positions. Champions have responded that the book touches on deeply buried wants (some say needs).

Splitting an argument into a false dichotomy is one of those fallacies that logic teachers try to beat into our heads, and the dispute over Fifty Shades is no different. Certainly, if you like it, you're not wishing for the return of women as chattel, or a diminution of hard-won rights. But maybe there's something to the popularity of a book about BDSM. Maybe women really do want to get a little kinkier in bed?

Every so often, sex becomes popular. Wait, let me re-phrase that. Every so often, talking about sex loses some of its taboo and the popular dialogue embraces a more nuanced approach. Kinsey gave us his eponymous report. The 60s taught us the joys and social dangers of lack of restraint. AIDS made us all terribly aware that pleasure has its physical price. While Fifty Shades certainly isn't a Kinsey report, it has unleashed a popular dialogue of sex that has been clouded by the book's abysmal quality.

Like the tulips' unqualified beauty was clouded by the avarice of short-sided men, perhaps the lesson we should learn from Fifty Shades isn't that people like to read really trashy fiction, but that they'd like to experience a fuller, deeper sexual experience. But first we have to be willing to talk about it.

So what's going on?

In 1841 Charles Mackay wrote a book called Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, describing the paroxysms of stupid into which people sometimes work themselves. His book popularized the strange phenomenon that occurred in the Netherlands in late 1636 and early 1637 when people went crazy for tulips. Sometimes called Tulipomania, at its height a single tulip bulb could sell for ten times the average income of a skilled craftsman. We recognize the phenomenon as an economic bubble, and we're still falling prey to it today. Mackay continues by examining a number of popular delusions to which we're still (more or less) prey: "alchemy, crusades, witch-hunts, prophecies, fortune-telling, magnetisers (influence of imagination in curing disease), shape of hair and beard (influence of politics and religion on), murder through poisoning, haunted houses, popular follies of great cities, popular admiration of great thieves, duels, and relics."

Now, while the tulip mania had some sort of basis in reality, and built on false hopes of government intercession, at its base it was an economic bubble. People were getting rich, and hoped that they would continue to get rich. So at least people were going dumb for something tangible. The rest is simple superstition, which nonetheless motivates more people than we'd like to account for. Recent statements by a Republican nominee seem to indicate that some people, as my training instructors liked to say, are still "stuck on stupid."

It would be irresponsible of me to conclude that fans of Fifty Shades are simply ill-educated or lacking mental faculty. The epithet of "mommy porn" has been applied to these stories often, and not just by literary detractors. Feminists have argued that this sort of depiction undermines much of their work over the last half century, relegating women to subservient positions. Champions have responded that the book touches on deeply buried wants (some say needs).

Splitting an argument into a false dichotomy is one of those fallacies that logic teachers try to beat into our heads, and the dispute over Fifty Shades is no different. Certainly, if you like it, you're not wishing for the return of women as chattel, or a diminution of hard-won rights. But maybe there's something to the popularity of a book about BDSM. Maybe women really do want to get a little kinkier in bed?

Every so often, sex becomes popular. Wait, let me re-phrase that. Every so often, talking about sex loses some of its taboo and the popular dialogue embraces a more nuanced approach. Kinsey gave us his eponymous report. The 60s taught us the joys and social dangers of lack of restraint. AIDS made us all terribly aware that pleasure has its physical price. While Fifty Shades certainly isn't a Kinsey report, it has unleashed a popular dialogue of sex that has been clouded by the book's abysmal quality.

Like the tulips' unqualified beauty was clouded by the avarice of short-sided men, perhaps the lesson we should learn from Fifty Shades isn't that people like to read really trashy fiction, but that they'd like to experience a fuller, deeper sexual experience. But first we have to be willing to talk about it.

Thursday, August 23, 2012

Amazon Hero Award

Every once in a while, I get irritated when someone disparages or dislikes something that I like. I have a lot of emotional energy tied up in the books, movies, music, etc., that I enjoy and hearing someone disparage them feels like an attack against me personally. So I get it. I understand that sometimes we all need to let off some steam. But sometimes we just need to take a long, calming breath and realize that these things don't really matter. The flame war by devout fans (and husband) of Emily Giffin are just really over the top. I mean, death threats? Really, people. Chill.

Anyway, I hereby nominate Corey A. Doyle for the Amazon Hero Award, an award which recognizes intellectual and moral courage in the face of social pressure on the internet. So way to go, Corey, for sticking up for yourself. I hope the cops catch the bastard.

Anyway, I hereby nominate Corey A. Doyle for the Amazon Hero Award, an award which recognizes intellectual and moral courage in the face of social pressure on the internet. So way to go, Corey, for sticking up for yourself. I hope the cops catch the bastard.

Uncharted 2: Among Thieves . . . It Stole My Heart

I know. That is a particularly bad title. Also, I'm sure you're probably asking yourself why I'm only now getting around to playing this game. The answer is simple. This is the first time I've had time, and a Playstation, with which to play it.

Let me go ahead and let you know that while this is specifically a review about the second installment of the Uncharted franchise, it's also more generally a review of the first one as well, since I purchased the Game of the Year dual-pack and played both games sequentially. Although, why would I have played them in any other order? Hmm . . . .

Overview

Regardless, I should probably start with my thoughts on third-person shooters.

I really don't like them. I find them clunky, unwieldy and aesthetically unpleasing. Why would I want to spend the next 10 or more hours staring at someone's backside? You know, unless it was a really nice backside.

Motion Capture

Naughty Dog, the game developers, went to a lot of trouble to make me want to stare at another guy's back-side for well over 20 hours. The motion capture in general is flawless, and all the more nuanced in the second game. Furthermore, this game includes a lot more freedom in movement than many third-person games I've played before. The camera rotates easily, and the cinematic feel of the game provides that you have more than ample opportunity to look at more than just Nathan Drake's backside.

Gameplay

Overall, the gameplay was remarkably smooth and enjoyable. A few times, even though a particular puzzle was not difficult to solve, making the character perform the requisite actions was excruciatingly ponderous. These were few, but noticeable (particularly in the first game, Drake's Fortune), but they hardly detracted from my enjoyment of the game once I resigned myself to dying a few times.

Game Design

As for the game design itself, it was beautiful. I can't review it glowingly enough. Each set felt immersive and the level of detail was simply stunning. My only complaint was the seemingly illogical construction of some of the sets. While I recognize that this is an action-adventure fantasy, many of the puzzles and locales simply didn't make any sense. Of particular note is the puzzle which requires you to point a beam of light at specific points to activate ancient machinery. While this might work with modern technology, I had a really hard time suspending my disbelief that a five-hundred-year old civilization had the know-how to get this up and running.

Monsters? Really?

Also, there are monsters. This was handled much more expertly in the second installment, but rather indelicately in the first. In a game more-or-less grounded in the real world, it felt like a betrayal to find out that Incan gold really is cursed. While they explained it (sort of) in game as some kind of infection, the more glaring plot holes (such as where all the infected people came from, or were we to assume that they were well over three hundred years old?) were never adequately filled in. In fact, the plot holes were so offensive that I stopped playing the game for nearly a week until my ire had subsided.

The monsters in the second game make a little more sense. Tied as they are to the abominable snowman (or yeti) myth, since the game is set in Tibet, I forgave the designers more readily. However, they handled their monsters much more adroitly, so my pique was short and quickly assuaged.

Brass Tacks--Story and Characterization

The story, however, and the characters, are what truly make these games phenomenal. Another developer could have gone a completely different route, and paid lip service only to a full fleshed out plot; or they could have invested less effort in voice and motion capture. The level of investment that Naughty Dog displayed is truly remarkable, and adds a level of believability, and ultimately, playability into the game.

In each game, you play Nathan Drake, who, in the first game, is a loveable rogue searching for the mystery of his forebear, the eponymous Sir Francis Drake, of privateer fame. The mystery, basically, is that Drake died childless--yet family history leads Nathan to believe he is his descendant. Tied to that, is the mystery of El Dorado, which Francis Drake seems to have discovered. So basically, you're on the hunt for the Golden City, plagued by baddies and trying to save both the day, and the girl.

The second time around pits Nathan against a warlord and a friend who betrayed him. The story deepens, however, by the introduction of a new girl in Nathan's life, and the absence of the female lead from the first story. In the second game, Drake is on the hunt for the lost treasure ships of Marco Polo, which lead him eventually to Shangri-la.

Morality? In a Video Game?

I suppose one of my major complaints about these two games are the moral ambivalence that each displays. Certainly, I'm not going to blame violence in video games for violence in the real world, but these types of games are woefully disinterested in the morality of wiping out thousands of people in the course of the adventure.

What is all the more worrying is the flippancy of it. Perhaps you can make some sort of an argument for self-defense, as the bad-guys probably shot first (but certainly not always, and your character often takes the killing hand-to-hand), but the game designers make very little effort to explain why the character is there at all. Beyond a nebulous sense of greed, that is. Because, ultimately, he is a treasure-hunter. A tomb raider; in the first game it is explicitly stated that Nathan Drake is killing people for the money. He wants the goods.

The violence inherent to most games has never bothered me. Modern Warfare is an example of a game that I love, the violence of which makes Uncharted pale in comparison. Yet, I assuage my moral sense with the belief that there is some sort of moral continuum. The bad guys are terrorists, the good guys are the forces of order. But even then, the terrorists have some sort of goal. They're part of a complex moral order that has been aggrieved. And while I probably disagree with their reasoning, at least they have one. Nathan Drake's moral order is unbridled avarice. And that bothers me. Monsters? Kill 'em. Aliens? Mow 'em down. But human beings? I'd like some nuance with my carnage, please.

Conclusions

Basically, I like these games. They're not perfect, but the pros definitely outweigh the cons and I would never hesitate to recommend these to a friend. Or even a perfect stranger.

Let me go ahead and let you know that while this is specifically a review about the second installment of the Uncharted franchise, it's also more generally a review of the first one as well, since I purchased the Game of the Year dual-pack and played both games sequentially. Although, why would I have played them in any other order? Hmm . . . .

Overview

Regardless, I should probably start with my thoughts on third-person shooters.

I really don't like them. I find them clunky, unwieldy and aesthetically unpleasing. Why would I want to spend the next 10 or more hours staring at someone's backside? You know, unless it was a really nice backside.

Motion Capture

Naughty Dog, the game developers, went to a lot of trouble to make me want to stare at another guy's back-side for well over 20 hours. The motion capture in general is flawless, and all the more nuanced in the second game. Furthermore, this game includes a lot more freedom in movement than many third-person games I've played before. The camera rotates easily, and the cinematic feel of the game provides that you have more than ample opportunity to look at more than just Nathan Drake's backside.

Gameplay

Overall, the gameplay was remarkably smooth and enjoyable. A few times, even though a particular puzzle was not difficult to solve, making the character perform the requisite actions was excruciatingly ponderous. These were few, but noticeable (particularly in the first game, Drake's Fortune), but they hardly detracted from my enjoyment of the game once I resigned myself to dying a few times.

Game Design

As for the game design itself, it was beautiful. I can't review it glowingly enough. Each set felt immersive and the level of detail was simply stunning. My only complaint was the seemingly illogical construction of some of the sets. While I recognize that this is an action-adventure fantasy, many of the puzzles and locales simply didn't make any sense. Of particular note is the puzzle which requires you to point a beam of light at specific points to activate ancient machinery. While this might work with modern technology, I had a really hard time suspending my disbelief that a five-hundred-year old civilization had the know-how to get this up and running.

Monsters? Really?

Also, there are monsters. This was handled much more expertly in the second installment, but rather indelicately in the first. In a game more-or-less grounded in the real world, it felt like a betrayal to find out that Incan gold really is cursed. While they explained it (sort of) in game as some kind of infection, the more glaring plot holes (such as where all the infected people came from, or were we to assume that they were well over three hundred years old?) were never adequately filled in. In fact, the plot holes were so offensive that I stopped playing the game for nearly a week until my ire had subsided.

The monsters in the second game make a little more sense. Tied as they are to the abominable snowman (or yeti) myth, since the game is set in Tibet, I forgave the designers more readily. However, they handled their monsters much more adroitly, so my pique was short and quickly assuaged.

Brass Tacks--Story and Characterization

The story, however, and the characters, are what truly make these games phenomenal. Another developer could have gone a completely different route, and paid lip service only to a full fleshed out plot; or they could have invested less effort in voice and motion capture. The level of investment that Naughty Dog displayed is truly remarkable, and adds a level of believability, and ultimately, playability into the game.

In each game, you play Nathan Drake, who, in the first game, is a loveable rogue searching for the mystery of his forebear, the eponymous Sir Francis Drake, of privateer fame. The mystery, basically, is that Drake died childless--yet family history leads Nathan to believe he is his descendant. Tied to that, is the mystery of El Dorado, which Francis Drake seems to have discovered. So basically, you're on the hunt for the Golden City, plagued by baddies and trying to save both the day, and the girl.

The second time around pits Nathan against a warlord and a friend who betrayed him. The story deepens, however, by the introduction of a new girl in Nathan's life, and the absence of the female lead from the first story. In the second game, Drake is on the hunt for the lost treasure ships of Marco Polo, which lead him eventually to Shangri-la.

Morality? In a Video Game?

I suppose one of my major complaints about these two games are the moral ambivalence that each displays. Certainly, I'm not going to blame violence in video games for violence in the real world, but these types of games are woefully disinterested in the morality of wiping out thousands of people in the course of the adventure.

What is all the more worrying is the flippancy of it. Perhaps you can make some sort of an argument for self-defense, as the bad-guys probably shot first (but certainly not always, and your character often takes the killing hand-to-hand), but the game designers make very little effort to explain why the character is there at all. Beyond a nebulous sense of greed, that is. Because, ultimately, he is a treasure-hunter. A tomb raider; in the first game it is explicitly stated that Nathan Drake is killing people for the money. He wants the goods.

The violence inherent to most games has never bothered me. Modern Warfare is an example of a game that I love, the violence of which makes Uncharted pale in comparison. Yet, I assuage my moral sense with the belief that there is some sort of moral continuum. The bad guys are terrorists, the good guys are the forces of order. But even then, the terrorists have some sort of goal. They're part of a complex moral order that has been aggrieved. And while I probably disagree with their reasoning, at least they have one. Nathan Drake's moral order is unbridled avarice. And that bothers me. Monsters? Kill 'em. Aliens? Mow 'em down. But human beings? I'd like some nuance with my carnage, please.

Conclusions

Basically, I like these games. They're not perfect, but the pros definitely outweigh the cons and I would never hesitate to recommend these to a friend. Or even a perfect stranger.

Wednesday, August 22, 2012

The Power of Story . . . And Its Curse

Why Story?

Narratives--stories--are powerful things. They offer us solace by delineating reality; they fence-in the chaos of our lives and permit us the ability to explain what is, essentially, inexplicable. Stories like these, the ones that explain the grand structure of our lives, are often called Myths. Myths that you might know as such explain why rainbows exist, why there is evil in the world, where babies come from. They are the most important stories because they give our lives order.

Smaller myths exist as well. These quotidian myths are no less compelling just because they lack the dignity of a capital letter. They explain the everyday--why is that person poor? Why do those groups of people hate us? Or why do we hate them? Ten thousand . . . a million more. How you choose to answer those questions reveals much about you, but as likely as not, you explained your answer in the terms of narrative. That person is poor because of some other external event. That's the power of narrative, for every action there is a cause. And a preceding cause, and a whole chain of them ad infinitum.

The Power of Story

As stories are re-told, though, something about their character changes. Instead of explaining the world--depicting how something is--they metamorphose into how people ought to react to the world. Once you've heard a certain number of times how your forebears reacted to an event, you begin to imagine yourself in that same position. How would you respond? Likely, you would respond the same way that those people did in the stories that you've been told.

This is the power, and the danger, of the human imagination; it is both the blessing and curse of story.

A story, in and of itself, is never dangerous. Even if its contents are seemingly malevolent, the moral content of a story if often imparted only after the fact. We used to be much more obvious about it, and we still sometimes ask what the moral of a story is. In common parlance it means something like the theme of the story, but it has a much more literal meaning when we think about how that narrative prescribes our actions.

Structure of Story--The Grand Myths

Thinking about this got me thinking about what stories we tell ourselves today. First, there is the grand, progressive narrative of history. In the Western tradition, at least, history leads ever upward toward human enlightenment and human liberation. It is a story of freedom from oppression of all types. Ultimately, it is a story of justice triumphing over caprice and maliciousness.

Buried within that story, or perhaps framed within it, is another, equally powerful story. It is the myth of capitalism (or of progress, expansion, ever-and-upward). This is a story we tell closer to home. It is a hearth story. Other people have a hearth story that embraces communism or socialism, or possibly some form of fascism. They are at once stories about how the world works, and stories of how we ought to work in the world. They are, at their heart, myths about how the world--and especially how our part of it--works.

Embedded even further in that myth, are the narratives of the people who occupy those regions. These are the stories that tell us how to confront and engage with outsiders, or with enemies, or with rival nations. They are the stories that teach us how to die dignified deaths, and how to relate ourselves to the state. Some of these stories are abandoned, as they ought to be, but others are re-appropriated and the moral changed. These stories, because they are more intimate, because they deal with the actions of real people you can relate to, are the stories that can change.

Narrative is not a panacea, nor is it an evil that once exorcised will cure the world's ills. It is a tool; and like any tool, it can be re-purposed.

New Narrative

Narrative is simply a social construct. And like all social constructs--like the economy, like race, like class--it can be changed. But only so long as the social will exists to change it. I propose that the growing emphasis on personal narrative at the expense of the national, or supranational, has damaged society. We call it tolerance, and multiculturalism, and indeed, each of these things is important. But more important than understanding our differences is understanding our similarities.

I'll say it again. I'm not so naive to believe this will solve everything. But I think it's a step in the right direction. I think that it has the potential to alter the way we see the world, and by changing our own vision, expand the way we imagine ourselves within it. To change something, first you have to imagine it another way. And that is the power of story.

Narratives--stories--are powerful things. They offer us solace by delineating reality; they fence-in the chaos of our lives and permit us the ability to explain what is, essentially, inexplicable. Stories like these, the ones that explain the grand structure of our lives, are often called Myths. Myths that you might know as such explain why rainbows exist, why there is evil in the world, where babies come from. They are the most important stories because they give our lives order.

Smaller myths exist as well. These quotidian myths are no less compelling just because they lack the dignity of a capital letter. They explain the everyday--why is that person poor? Why do those groups of people hate us? Or why do we hate them? Ten thousand . . . a million more. How you choose to answer those questions reveals much about you, but as likely as not, you explained your answer in the terms of narrative. That person is poor because of some other external event. That's the power of narrative, for every action there is a cause. And a preceding cause, and a whole chain of them ad infinitum.

The Power of Story

As stories are re-told, though, something about their character changes. Instead of explaining the world--depicting how something is--they metamorphose into how people ought to react to the world. Once you've heard a certain number of times how your forebears reacted to an event, you begin to imagine yourself in that same position. How would you respond? Likely, you would respond the same way that those people did in the stories that you've been told.

This is the power, and the danger, of the human imagination; it is both the blessing and curse of story.

A story, in and of itself, is never dangerous. Even if its contents are seemingly malevolent, the moral content of a story if often imparted only after the fact. We used to be much more obvious about it, and we still sometimes ask what the moral of a story is. In common parlance it means something like the theme of the story, but it has a much more literal meaning when we think about how that narrative prescribes our actions.

Structure of Story--The Grand Myths

Thinking about this got me thinking about what stories we tell ourselves today. First, there is the grand, progressive narrative of history. In the Western tradition, at least, history leads ever upward toward human enlightenment and human liberation. It is a story of freedom from oppression of all types. Ultimately, it is a story of justice triumphing over caprice and maliciousness.

Buried within that story, or perhaps framed within it, is another, equally powerful story. It is the myth of capitalism (or of progress, expansion, ever-and-upward). This is a story we tell closer to home. It is a hearth story. Other people have a hearth story that embraces communism or socialism, or possibly some form of fascism. They are at once stories about how the world works, and stories of how we ought to work in the world. They are, at their heart, myths about how the world--and especially how our part of it--works.

Embedded even further in that myth, are the narratives of the people who occupy those regions. These are the stories that tell us how to confront and engage with outsiders, or with enemies, or with rival nations. They are the stories that teach us how to die dignified deaths, and how to relate ourselves to the state. Some of these stories are abandoned, as they ought to be, but others are re-appropriated and the moral changed. These stories, because they are more intimate, because they deal with the actions of real people you can relate to, are the stories that can change.

Narrative is not a panacea, nor is it an evil that once exorcised will cure the world's ills. It is a tool; and like any tool, it can be re-purposed.

New Narrative

Narrative is simply a social construct. And like all social constructs--like the economy, like race, like class--it can be changed. But only so long as the social will exists to change it. I propose that the growing emphasis on personal narrative at the expense of the national, or supranational, has damaged society. We call it tolerance, and multiculturalism, and indeed, each of these things is important. But more important than understanding our differences is understanding our similarities.

I'll say it again. I'm not so naive to believe this will solve everything. But I think it's a step in the right direction. I think that it has the potential to alter the way we see the world, and by changing our own vision, expand the way we imagine ourselves within it. To change something, first you have to imagine it another way. And that is the power of story.

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

H+ Review . . . Style Without Substance

New Digital Series Released by Warner Bros.

Bryan Singer, the guy responsible for "Superman Returns," "X-Men," "X2" and "The Usual Suspects," has recently unleashed his new digital series "H+." The plot is simple. Sometime in the near future a nanotech corporation invents a way to port the internet directly into people's brains. No more iPhones, no more tabets, because you're always on-line. Predictably, things go wrong, someone hacks the servers and, yep, people start dying.

Warner Bros. distributed the first two episodes beginning August 8, but if you subscribe to the channel you can view an additional four episodes.

The first episode gives us a rough background on the story, with nice visuals and fine production value. At just over seven minutes, the first episode is slightly longer than the (thus far) usual five minute running time the episodes average. It begins in an underground parking structure in San Fransisco with a fight between husband and wife--the stereotypical argument about a guy failing to turn off the game once he's been told.

Driving deep into the bowels of the structure, they soon lose service, cutting them off from the internet. After nearly hitting a man seemingly fleeing for his life, they suddenly realize that people are dropping dead just a few hundred feet in front of them. Then a plane crashes on them. It's all too quickly revealed that someone hacked the net and planted a software virus to kill people. The few survivors are only safe as long as they remain out of service range.

The remainder of the episodes are very quick vignettes, neither full stories nor seemingly connected to one another except for the time stamp at the beginning which references where the action takes place, and the temporal reference post- and ante- "Event."

Despite the stellar performances thus far, the beautiful CG, and a dystopian story of seemingly apocalyptic scope, I have a hard time believing this is going to go anywhere.

As I've mentioned before, the average episode is about five minutes long. Hardly enough time to even establish location, it's woefully inadequate for expressing story or delivering characterization. In the six episodes that have been released, only two follow the same characters. The inherent shallowness of the storytelling strikes me as inimical to the success of the show as a whole. Released once a week, I have a hard time believing that anyone will stick around long enough to see where its going.

And really, we've already heard this story. It's a science-fiction trope that new technology will go bad in the worst possible way. Maybe Singer hasn't done his homework, or maybe he thinks he has something new and important to say. But so far, I'm not convinced.

Monday, August 20, 2012

R.I.P Tony Scott

According to news outlets, Tony Scott, director of films such as "Top Gun" and "Crimson Tide," and "Man on Fire," died early this morning in an apparent suicide. According to officials, he left a note in his car before jumping from Vincent Thomas Bridge in San Pedro, California.

With his older brother, Ridley Scott, he created Scott Free Productions in 1995. Since directing "Top Gun" he's been behind the helm of many of the films that defined my sense of summer action blockbusters. "Crimson Tide" and "Enemy of the State" stand out as pivotal films that altered the way I perceive the role of government and, in the case of "Crimson Tide," war itself.

He was a great director, and with his brother (notably as Executive Producer for "Prometheus"), helps define the genre of science fiction for the big screen. His will be a sorely missed presence.

Stargate: Universe . . . The Review

I just finished watching Stargate: Universe on demand on Netflix and I have to tell you: It doesn't suck.

I started watching Stargate: SG1 when it premiered on TV, and then stopped after a few episodes, but I eventually picked it back up on DVD. I watched nine seasons worth before I gave up on it as being silly, contrived and with diminishing production values. Then suddenly they were talking about going to Atlantis, of all places, and I decided to let it go.

But I came back to SG: Atlantis about halfway through the second season and I was intrigued enough to give it a shot. But it was just as silly and contrived as as SG1 so I stopped.

Then SG: Universe came out. By then I was so jaded that I couldn't conceive that the show would be any good, even though some of my friends said it wasn't bad. But they weren't excited about it, so that was a sure sign for me to let sleeping dogs lie.

Recently it popped up on Netflix on demand, and I figured I'd give the pilot a try while I folded laundry. Thank god for laundry, I have to tell you. If I'd devoted my attention to the first ten minutes or so, I probably would have turned it off. With cameos from the SG1 cast, and with the same hackneyed acting I would have stopped watching and never looked back. But I wasn't paying attention. Sometime between folding all my underwear and staring on the towels, the show got good. It got really good. So good that I had to rewind, put the laundry to the side and sit down to watch.

Basic premise: bunch of people stranded on a ship in the middle of nowhere with no hope of rescue. The ship itself, however, is falling apart and their presence has only exacerbated the problem. So within the first moments they have to learn to work together to fix the ship while fighting panic and learning how the new world works. Immediately, a critical moral quandary arises. And someone important dies. Just like that. It proved that it had the chops to make the hard calls in the first hour and it has maintained those chops throughout the first two seasons.

Will it fall into ignominy and victim to the silliness of Atlantis and SG1 prior? Perhaps. The potential certainly exists. Several stories have been borderline abysmal. But when it excels it really excels. Of particular note is the way in which it deals with time travel. Yeah, time-travel; we know the trope and we know that most shows do it very poorly. Even Dr. Who has its problems and its a show predicated upon traveling through space and time.

But SG: Universe does it with aplomb.

First, it lays out the ground rules, rules already established in SG1. They're silly rules, and feel like the arbitrariness of a bored writer in a hurry. Nevertheless, this is the continuity in which the story exists, so that's how this show will play the game. But it treats those rules with respect and examines the ramifications of each instance, following them along lines of reasoning that have dire moral implications. It isn't shy about it, either. Paradoxes are treated with respect, and made integral to the character's progressions.

Ultimately, this is a show about the characters. Well rounded characters have always made for good television. More than stereotypes--the nerd, the pretty girl, the corn-fed American soldier-boy, tough-as-nails black man, stern leader--these characters have foibles, flaws and, more often than not, virtues. But when they err, people die. Though sometimes those deaths are caused by negligence, caprice or simple exhaustion, it is always on the part of the characters, and not the story writers.

So, while at first I was surprised that it was good for an iteration of Stargate, have come to love it as being good in its own right. You should give it a chance, it's on Netflix.

Friday, August 17, 2012

Best Sci-Fi/Fantasy Baddy . . . Skeletor v. Darth Vader

Skeletor Vs. Darth Vader

Both of these guys are characters from my childhood. I watched He-Man as a cartoon on Saturday mornings and Star Wars just about every night on VHS. Both are bad-ass, and both are pretty damn creepy. So here I pose to you, Awesome Reader, who do you think would come out in a one-on-one grudge-match? This isn't like any of those other pansy contests you've seen on the interwebs. This one's got merit. Both are evenly matched, and the conclusion is anything but preordained.

Skeletor

So what if he started existence as an action figure? So what if he's usually depicted as a blue guy wearing (what appear to be) furry underpants? He sacrificed his face to keep on going, and now he takes on He-Man in the on-going battle for Greyskull Mountain to gain unlimited power and conquer all of Eternia.

Let's talk about his powers and abilities. First of all, he's a sorcerer, he can shoot lightning out his hands, he can teleport himself and his minions and he's cunning and very intelligent. And as wikipedia puts it, he's "privy to much secret knowledge about the universe." On top of that, he's got the Havoc Staff, a staff-weapon that discharges bolts of mystic energy. And hey, he's a more than decent swordsman on top of all that. That'll come in handy when our two boys square off.

Darth Vader

That scene of him entering the rebel cruiser for the first time, smoke in the air, dead stormtroopers lying around him, black-as-sin cape swirling around him . . . oh my. Still gives me goosebumps when I see it. Then I remember that pitiful scream of loss and rage at the end of Episode III and I hate George all over again. But Darth Vader as I first remember him, he's the incarnation of evil and that's who we're going to put up against Skeletor.

Powers? He's got the Force. He can manipulate space and people's will. He can kill at a distance and has prescient knowledge of the future. He has an absurdly baritone voice. Sure, that's not technically a power, but I'm giving it to him anyway. He's a pretty baller pilot even if he can't hit an X-Wing Fighter flying down a narrow canyon right in front of him! Is it like pod-racing now, Ani?

He made his own lightsaber which can cut through flesh and bone and plasteel, and although we're told that he's a pretty good swordsman, I've seen him battle Obi-Wan and it wasn't all that impressive from where I was sitting. But hey, he got better by Jedi. On top of all that, even though he can't shoot lightning out of his fingers, he sure can take some. And tossing his lord and master down an abyss to save his son proves, even if they are "more machine now than man," that he's got balls.

Round One: Fight!

Let me know what you think. Rules are simple, Masters of the Universe (1987) continuity for Skeletor, and Episodes IV, V, VI for Vader (no books, comics, games, or whatever else from the extended universe).

There will be three rounds and whoever gets the most votes wins that round. Voting continues for a week or so. Get creative and have fun: post your vote in the comments below.

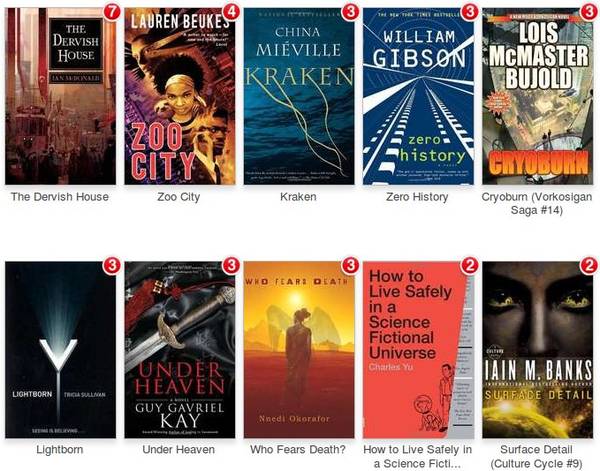

What Good's An Award If No One Knows About It?

Awards

Recently a buddy of mine commented that until he started hanging out with me he never knew that there were literary awards. He's not sheltered, nor was he raised in a barn, nor on Mars and only recently been returned to teach us the Martian ways of peace and "grokking."

Anyway, it got me thinking that maybe the world of genre awards are kind of like Employee of the Month awards. They're great, and they acknowledge your good works but the only people who see them are fellow employees. Normally they're tucked away somewhere near the bathrooms, or by the employee break area.

Sciencefictionworld.com has a great guide to previous years genre award winners, be they fantasy or sci-fi, and I encourage you to go take a look.

Let me know what your fave sci-fi or fantasy is in the comments.

Thursday, August 16, 2012

H.P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard . . . Embarrassing Middle Names

Last night I found two great collections of both Lovecraft and Howard's works. Both are electronic editions of the collected works of Lovecraft, and the collected Conan stories by Robert E. Howard. Howard wrote other things, but this was the first time that I had seen all of the Conan stories in a single place. Normally, they're broken up into separate volumes and at $15 a pop can add up pretty quickly. Barnes and Noble has a delightful collection of Lovecraft's stuff, and even though it has a beautiful leather cover I can't seem to work up the hutzpah to plop $30 down on it. On my Kindle, however, each went for less than $3--the Conan collection itself was less than a buck.

Last night I found two great collections of both Lovecraft and Howard's works. Both are electronic editions of the collected works of Lovecraft, and the collected Conan stories by Robert E. Howard. Howard wrote other things, but this was the first time that I had seen all of the Conan stories in a single place. Normally, they're broken up into separate volumes and at $15 a pop can add up pretty quickly. Barnes and Noble has a delightful collection of Lovecraft's stuff, and even though it has a beautiful leather cover I can't seem to work up the hutzpah to plop $30 down on it. On my Kindle, however, each went for less than $3--the Conan collection itself was less than a buck.So what does that mean, other than that I am a tightwad over really inconsequential things? First, it's an indictment of the way publishers market and sell their books. Second, its an interesting meditation on the way in which works of fiction are consumed. Well, let me clarify that. It's an interesting meditation on the way in which written works of fiction are consumed. Both of these works were published in the early twentieth-century. Some of Lovecraft's works are old enough to have passed into the public domain (though I think Miskatonic or Arkham keeps the copyright alive). Conan is a part of the modern gestalt.

On some levels, this means that Cthulhu and Conan belong to the public in a way that most modern writers have a hard time wrapping their head around. J.K. Rowling (another author known only by her last name. I'm sensing a theme) understands this, and is probably a good example of a modern author who has allowed the public to both consume and take ownership of her works. She knew when to let go. George Lucas (no mysterious middle initial here) is probably the best example of the opposite way of going about it. He maintains such tight control that his fans have actively begun working against him

Both of these phenomena converge in a hazy middle ground between the authorial instinct to conserve their creation, and the consumers' instinct to embrace and propagate beloved story. This comes out in the medium itself. At least within publishing, there are certain overhead costs that simply must be paid. Printing, storage, and shipping are the few that comes easiest to mind, but certainly they are not alone.

I remember hearing with almost rapturous delight about the coming age of the e-book. Certainly if we are not already in it, we can just see it over the horizon. And it casts a long shadow indeed. We were told to expect that publishers would slash their prices, and that the heady forces of the free market would drive prices to unfathomably low levels. Strangely, that never occurred.

Maybe it wasn't so strange, after all, though. Maybe it's something like the George Lucas phenomenon. Is it possible that publishers are holding on too tightly? I have a feeling it's more than possible, it's probable that the publishers are squeezing their fists. And we don't need Princess Leia to tell us that tighter they close it, the more star-systems will slip through their fingers. Or book sales. You get the point.

Don't get me wrong. Unrestricted consumerism never solved any problems, either. Letting the horses have a free reign is nice for a weary horse, but dropping the reigns entirely means you'll probably plummet over a edge cliff when something spooks them. Market forces are a lot like that, and publishers need to figure out that lowering prices (but not slashing them) is the best way to bring back jaded and weary consumers. The stunning success of Fifty Shades of Gray (I feel a little filthy dignifying them with italics) proves that point. Initially published entirely online, they were adopted as print editions to satisfy the decreasing, but still substantial, niche of readers who will only partake in masses of battered wood pulp splattered with toxic chemicals.

I have to admit, I privilege the printed book over the electronic. But gradually, as the ease of consumption increases, I have turned much more readily to electronic editions. Which makes me suspect that books aren't dying, just printed books.

What do you think? Like some E? E-book that is. Let me know in the comments.

As a short addendum. It was really hard finding a picture of anything relating to Robert E. Howard and Lovecraft in the same picture. How great would a painting of Conan vs. Yog-sothoth be?

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Another Hugo Update . . . Miéville For The Win!

Who's Gonna Win the Hugo? This Guy . . .

It says it on the cover: "A fully achieved work of art." These are Ursula K. Le Guin's words, and I have a hard time thinking of someone better qualified to make that sort of pronouncement. Moreover, China Miéville reads a bit like Le Guin at her best. I don't mean to compare the two, but that same sense that the author is doing something truly original not only with the story but with the bounds of language itself.

Because Embassytown is a story about language. About what it means to relate meaning through simulacra, these noises that we emit and, arbitrarily and through common use, agree actually have meaning. Much of the story revolves around Avice, a human woman who has become a simile in the language of the Arikenes, the indigenes of strange alien world where the village of Embassytown has been constructed. In this alien tongue, only two things are immediately apparent--they cannot lie and they cannot understand us.

In order to facilitate communication, the Arikene (or Hosts, as the story calls them) enact elaborate rituals to create new ideas. Avice, the protagonist, is a particularly useful simile. Notorious for being the only member of this society to have ever left and returned to the godforsaken hinterland, she bears the fame of her similification uneasily, especially when she realizes that she has created a paradox within the Host society that may very well tear it apart.

Finally, human beings have reached a partial solution to the communication breakdown. The solution, however, requires human cloning, techno-pyschic pair-bonding, and psychological training to allow two individuals to think--and then speak--with the same mind. These pair-bonded individuals provide the vital link between the human colonists of this world and the alien indigenes, whose cooperation and largess they require to make any sort of life there.

Then something unexpected happens, and the very fabric of their society is torn apart.

If that last sentence sounds a bit melodramatic, that's because it is; but it's hard to express the sudden turn that Miéville weaves into the narrative without divulging much of what makes the book so unique. Because the sudden and terrifying arrival to their society is not all that terrifying. The world itself changes so that you can divide the book easily into before and after. This is the type of dramatic turn that is both unexpected and deeply satisfying, because it is both internally consistent with the fictional world that he has created, and subtle enough that you probably didn't see it coming--yet nonetheless had to have been.

Embassytown isn't as abstruse as some of Miéville's earlier works, especially Perdido Street Station and The Scar. Some of the flair and gusto is gone, leaving a stripped-down story comprised of pure characterization and plot, and the bare essentials of world-building. Don't get me wrong, what's there is pure Miéville and is all the more delightful for the economy with which he parses the world to the reader.

In the end though, Embassytown is a gentle meditation on language, both its limits and its potentially infinite variety; as such, it transcends genre expectations and revels in the delight of fine storytelling.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

The Doctor's Got a New Lady

|

| http://i2.cdnds.net/12/23/618x339/tv_doctor_who_matt_smith_jenna_louise_coleman_on_location.jpg |

If she looks familiar to you, that's because she was also in Captain America: The First Avenger. Announced today, twenty-five year old Jenna-Louise Coleman will star beside Matt Smith as the Doctor's new companion. You can read all the juicy details here, but suffice to say she's got to be amazing to replace Karen Gillan. Great companions come around rarely, and David Tennant had his fair share of really abominable companions. So hopefully the writers and producers will be able to craft a really stunning character for her.

Monday, August 13, 2012

Why the Olympics No Longer Matter . . . (To U.S.)

|

| http://www.joystiq.com/2012/07/30/official-olympics-game-takes-gold-on-uk-charts/ |

There's something of a pun in the title to this post, and for that, I apologize. It presented itself to me like a beggar on the street and I just couldn't refuse it.

Be that as it may, now that the 2012 Olympic games are over, I'm left with a feeling of ambivalence. There's a giant, "eh," resounding through my mind, and I imagine myself shrugging every time I talk about the Olympics.

Certainly, not everyone feels the same way. According to the Nielsens (those whacky guys that count who's watching what) this year's viewership surpassed the Beijing games by four million viewers, and this year's closing ceremonies were watched by thirty-one million people in the United States.

Viewership was probably aided by the fact that NBC poured expense and time into the events, adding 2,000 hours to coverage compared to 2008's Beijing Games. According to the Nielsen's this was the largest viewership in 36 years, making it the first time since the Cold War that anyone in the United States seems to have cared about them.

Now, that's a gross generalization. A lot of people invest countless hours into training for the Olympics every year; they pour their hearts and souls into the competition; and many more can't wait to see them compete.

But the Olympics have shifted meaning since the Soviet Union collapsed and the United States emerged as the world's dominant superpower. Since then, consumerism has risen to unprecedented, and probably unforeseeable, levels. Sports have come to symbolize something other than individual attainment, or the perfect embodiment of national zeal.

I remember being a child in the thrall of the Cold War. I remember going into a library and finding a book that said that the USSR had something like three times as many ballistic missiles as the United States, or a million more men in the army, or some preposterous thing like that. (I exaggerate or under-emphasize actual numbers due to the fact that I was 7 at the time and can't remember the exact numbers.) I remember feeling outraged that they had beaten us at something. Yes, I remember thinking in Manichean "us-them" terms. Some of you may remember Rocky going to the Soviet Union to absorb a couple of Dolph Lundgren's 2,000 lb/square inch blows. Or those pesky MiGs that just won't leave Maverick alone. That's the zeitgeist.

The United States, at that time, had invested a great deal of energy into beating the USSR in any and every possible field. We can see that reflected in Olympic viewership and the subsequent fall when the Soviet Union dissolved. We didn't have anyone to fight. Now, who's left? China? Maybe, but the ardor is missing from that rivalry.

What we're seeing in the spike in viewership, aside from the 2,000-and-some-odd hours of additional coverage (which no doubt matters) is the resurgent need for America to be good at something. We're not terribly good at empire-building (as evidenced from Iraq and Afghanistan), and we haven't quite got this post-industrial capitalist thing down, either. We're a nation adrift, demanding to be reminded that we can be great at something.

But because we're a post-industrial nation, and long down the consumerist track, the Olympics no longer really matter. It's interesting, and telling, that the primary American sport is not represented at the Olympics. Football pulls in numbers of viewers comparable to the closing ceremonies every week. The Super Bowl alone is a national holiday, and the players we have elevated to demi-god status amass levels of wealth so unseemly that it beggars both belief and credulity. Nonetheless, American football is unrepresented in the Olympics. Is it because only one country in the world could field a team? Or is it because football represents something inherently American--something that defies the cosmopolitan goals of the Olympics?

Because this isn't a blog post about why American football should be included in the Olympics, but rather my own musings about why the Olympics no longer matter (or perhaps, might soon matter again), I'll restrict myself here. But suffice it to say that there is something inherently American to our version of football that is repellant to the Olympic games, and that is our propensity to cheapen sport by turning it into another form of consumer good.

Professional athletes are themselves goods--turned into commodities, packaged, and finally sold to the public for our own entertainment. No more so than college athletes whom we have deluded into thinking that at least they'll get an education out of the deal. Highly paid, worshiped and adored, nevertheless, our professional sports suffer from the fact that they are goods to be bought, sold and traded. The vocabulary itself reflects this reality as players are yearly traded from one team to another--they are the living manifestation of their own trading cards.

But that's a little metaphorical, and I'm trying to keep this on the ground. The reason this all matters, though, is because Olympians, with a few exceptions, do not compete for our amusement. Their struggles throughout the years are entirely personal. So, with the gradual commodification of sports in the post-Cold War era, the meaning of the Olympics shifted. Olympic athletes could not be commoditized and so became unimportant.

Now, as the blows to American self-esteem strengthen, or as American nationalism re-surges because of internal, economic adversity, once more we'll see the Olympics start to matter again. In fact, I'd go so far as to opine that as we return to a worldview of "us-v.-them" (regardless of who they are) we'll once more see viewership of the Olympics on the rise.

Sunday, August 12, 2012

Batman: Puppet Master

With the end of the Christopher Nolan's Batman trilogy, I thought the Dark Knight was done until the next franchise re-boot. And since I've never given credence to fan films I doubt I would have stumbled across this on my own. But Nolan's universe is still alive and kicking. Pairing the ventriloquist and Scarface up with E. Nigma was a stroke of genius, and the acting of the ventriloquist was more than enough to watch this video. I'd never given much thought to seeing a live-action sequence with a tommy-gun toting dummy, but after this I think it might be worth a spin.

Hugo Update . . . And What's In An Award?

Right now, I'm about halfway through this year's Hugo nominees. Among Others, and Leviathan Wakes are pretty good. Since I still have yet to read more than the first hundred pages of Games of Thrones, I'm not really qualified to comment on A Dance with Dragons. That really just leaves Embassytown with the third installment of Mira Grant's Deadline series.

First of all, the Hugos are not like a Pulitzer or Nobel Prize. The first recognizes great American works of literature, and the second rewards an author's life work--the Noble Prize, in other words, rewards the entire oeuvre.

When I was a kid, and played little league, we'd end the season with a pizza party and golden trophies. Everybody got one and it symbolized your participation much more than your particular contribution. Now, I'm not saying that the legitimate efforts of highly talents people shouldn't be rewarded

The Hugo Award was set up to reflect popular trends in genre fiction. As such, it reflects what people like, as opposed to what is good. Now, don't get me wrong, many of the Hugo awards have been granted to exceptional works of fantasy or science-fiction. But what makes good genre fiction is not necessarily what makes good literature. At the heart of it, good literature challenges both the reader and the author. First the author must transcend the limitations of the medium to explore the bounds of human nature. The reader, on the other hand, must equally endure.

Michael Cunningham, one of the triad of jury members picking this year's Pulitzer Prize in fiction, explains at the New Yorker some of what went into choosing three titles from more than 300. What was so remarkable about his article, however, was not the behind-the-scenes work of jury members, but really he philosophy of what a particular award signifies.

He says that "[fiction] involves trace elements of magic; it works for reasons we can explain and also for reasons we can’t. If novels or short-story collections could be weighed strictly in terms of their components (fully developed characters, check; original voice, check; solidly crafted structure, check; serious theme, check) they might satisfy, but they would fail to enchant. A great work of fiction involves a certain frisson that occurs when its various components cohere and then ignite. The cause of the fire should, to some extent, elude the experts sent to investigate."

What this tells me, however, is that the utterly ineffable parts that Cunningham and his co-jurors suspected of greatness did not ignite a fire in the souls of the board members. So I'm curious how other awards will fare.

Will, for instance, A Dance With Dragons beat out China Mieville and Jo Walton? Each of these books has brilliance lurking between their lines, but G.R.R. Martin is the old favorite, and his series has recently received a boost in popularity with the made-for-premium-cable television series based on his books. Certainly, a spike like this can't be bad for Martin, but is it necessarily good for the Hugos?

Extending this line of thinking a little, Leviathan Wakes is the first book in an expected trilogy. Should we even consider something admittedly unfinished?

Perhaps it doesn't matter, though. Maybe this is an opportunity for the community to express its collective happiness with a particular author or work. Maybe its a moment for sci-fi and fantasy geeks to acknowledge their favorites and just celebrate with one another their own, personal pleasure at being part of the process. Because ultimately, awards are as much for the audience as they are for the recipient. That little trophy (be it a golden man, a rocket, or a golden bucket of popcorn) symbolizes that we enjoyed something. And we want you to know it.

So maybe the Pulitzer board already has life figured out and they don't need the challenge a good work of fiction symbolizes. Or maybe they're so far removed from the American experience that they no longer recognize it when it's staring up at them from the pages of very fine works. Either way, we'll still smile, and clap and cheer ourselves on and reward the fiction that we love.

Thursday, August 9, 2012

2012 World Fantasy Award Nominees

Check it out! The World Fantasy Award Nominees were just announced.

A Dance with Dragons by G.R.R. Martin made the cut, as did Among Others by Jo Walton. If you'll recall, both were nominated for the Hugo award this year.

Stephen King makes an appearance, which shouldn't surprise too many people (well, maybe it will because he's not particularly well-known for his fantasy works).

The real surprises are the books that haven't made much of a splash in the genre world. Osama, by Lavie Tidhar seems like something to keep an eye out for, as well as Those Across the River by Christopher Buehlman.

I'll let you know what I think but until then, post your thoughts in the comments.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)